German psychologists and the scientific case against prostitution

“Prostitution is in no way a job like any other. It is degrading, torturous, exploitive. On the side of the prostituted, there is a lot of horror and disgust at play, which they have to repress in order to get through it at all.” So says Michaela Huber, psychologist and head of the German Society for Trauma and Dissociation.

“In this system of prostitution, women are systematically put down, used, and degraded into objects.” So says Lutz Besser, head of the Centre for Psychotraumatology and Trauma Therapy of Niedersachsen.

“Prostitution has its roots in the violence that is done to children. And society must not block out or whitewash this violence!” So demands Susanne Leutner, vice-president of the trauma-therapists’ association, EMDRIA.

Leading German trauma therapists speak out sharply for societal awareness and support the “Stop Sex-buying” initiative. The organization, a coalition of citizens and centres of expertise, demands that johns be punished, in line with the Swedish model: “It is our goal, not to criminalize the prostituted, but to turn the focus on the johns, whose demand creates the market. They are actually responsible for the fact that increasing numbers of young women from the poorest countries in the world are brought to Germany to work in prostitution here.” Because “The reality of women in prostitution is being glorified or trivialized and ignored — and the sexual exploitation of women in this manner is being normalized and cemented.”

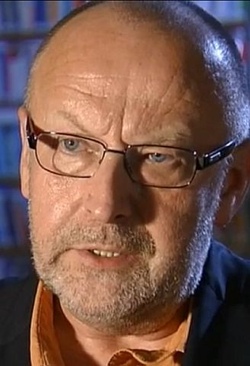

This offensive position in the treatment of traumatized persons by specialized therapists is, to put it mildly, a sensation. Among the therapists who have joined the initiative is Prof. Günter Seidler, head of psychotraumatology at the University of Heidelberg and a pioneer of German trauma research. “There are already more than enough psychologically traumatized people. The mental wounds of prostitution are avoidable,” says Seidler, one of the first 90 signatories of the EMMA appeal to do away with prostitution.

“Prostitution is violence, not a profession!” charges Prof. Wolfgang U. Eckart, director of the Institute for History and Ethics in Medicine at Heidelberg, in the journal Trauma and Violence. He argues: “Little is free in prostitution on the whole, and nothing in mediated prostitution. Because the striking asymmetry of power and the potential for violence in the relationship between the mediator and the practitioner generates in this oldest form of the enslavement of women constitutionally dependent relationships, which almost automatically deliver all the façades and backgrounds for the practice of traumatizing acts of violence of every sort.”

Dr. Ingeborg Kraus is the initiator of the therapists’ protest. The trauma therapist from Karlsruhe has dealt with victims of war rape in Bosnia, and after her return to the German trauma clinics, she realized: “Even here, every other female patient has experienced sexual violence.” At some point, Kraus got fed up with the “constant task of patching them back together”. She vowed: “I want to work preventively as well!” For her, too, the fight against prostitution is part of that. “In my long years of psychotherapeutic experience, I have accompanied prostituted women and learned their backgrounds. It thus became clear that prostitution was, in all cases, the continuation of violent experiences in their biographies.”

Michaela Huber can only confirm that, from her own therapeutic experiences and those of “many, many colleagues.” “Who even gets the idea to sell their own body? The prerequisite for that is to be alienated from one’s own body.” She continues: “You have to picture it: One has to let oneself be penetrated, again and again. One has to have practiced it, or one can’t do it. One leaves behind just a shell that can still go through certain motions, certain gestures.”

This beaming-oneself-away — dissociation, in specialists’ jargon — is forcibly learned, early on, by victims of violence. Not coincidentally, studies show that the majority of women (and men) in prostitution have suffered sexual abuse or other traumatic violence, eg. neglect, as children.

Traumatologist Lutz Besser demands a rethink of the acceptance of prostitution. He fears that “we are in danger of sliding into an Ice Age of ethics. Morality is one part,” says Besser. “But ethics also poses the question: What happens to another person if I do something?” This question, however, is one the johns don’t ask. “The men who go to prostitutes don’t realize that most of the women in this trade are doing so under pressure and duress. A society that legitimates that, demands the stance that prostitution is the most normal thing in the world,” says the therapist. “And it is a scandal that we as a society don’t have a clearer position on this!”

In Berlin, politicians are currently seeking advice. Not only as to how prostitution should be legally regulated; they will also decide how our society stands in regard to it: Whether prostitution should continue to be “a job like any other” — or whether prostitution goes against human dignity and destroys human beings. The signatory therapists hope that the politicians don’t just consign even more traumatized people to them, but finally take the side of prevention.

The Appeal has been also translated into Spanish and Italian.